Biophilic design is no longer considered an aesthetic trend; it is a performance-driven framework grounded in research that demonstrates measurable benefits to human health and productivity. By designing with nature in both structures and harmonious interior environments, architects and designers can boast a quantifiable return on investment in terms of reduced sick days (saving employers up to $3000 per year, per employee), improved productivity, and well-being. Studies by Terrapin Bright Green, the World Green Building Council, and Yale professor Stephen Kellert have shown that access to natural elements reduces stress, lowers blood pressure, increases cognitive function, and enhances creativity. For architects and designers, these findings underscore the importance of integrating biophilic strategies into every phase of the design process—from site orientation to interior detailing.

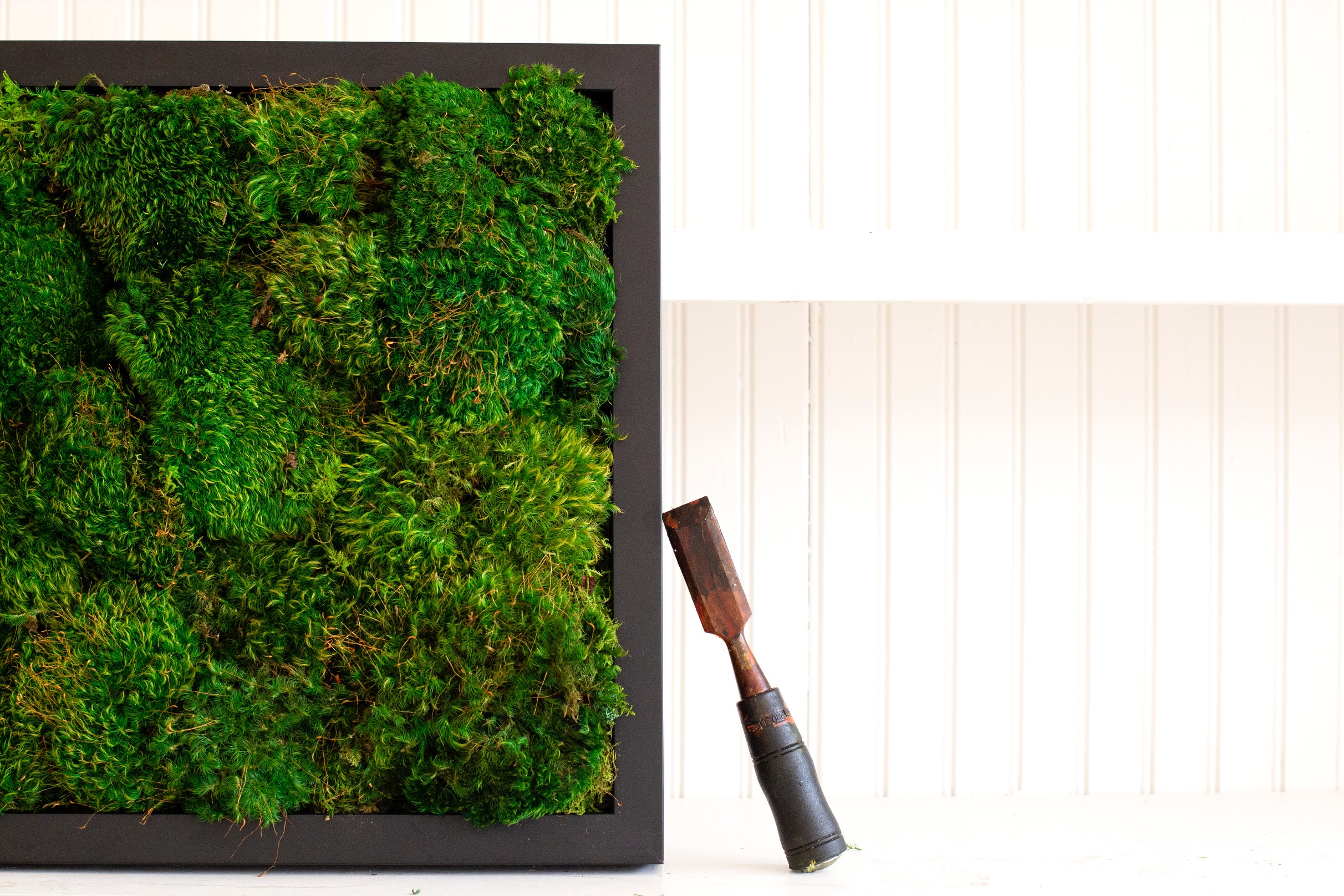

These pillow moss panels not only enhance aesthetics but also separate the workspaces and dampen noise.

1. The Nature of the Space

Windows as Frames for Living Art

According to the research paper The Economics of Biophilia (Terrapin Bright Green, 2012), views of nature from interior spaces can increase productivity by up to 6% and reduce stress-related absences by 10%. Designing fenestration as “frames” for natural vistas—whether tree canopies, gardens, or sky—allows occupants to engage with the changing qualities of light and season. Early-stage daylighting and glare analysis tools should be applied to optimize solar orientation and harness natural beauty as an integral design element.

Windows are frames for the outdoors and the moss frames connect the outdoors with the indoors in this bustling dental practice.

Blurring Interior and Exterior Thresholds

Architectural strategies such as transitional spaces, indoor gardens, or the use of continuous material palettes between exterior and interior diminish the perceptual boundary between built and natural environments. Kellert’s Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (2008) emphasizes that permeability and connection to context are essential in creating environments where humans feel a sense of place.

Integrating Living Energy with Greenery and Moss Walls

While living plants contribute oxygen and vibrancy, preserved moss walls and designs provide a low-maintenance solution with significant biophilic benefits. Moss walls require no irrigation, misting, or daylight and can be installed in areas where live plants cannot thrive. Beyond convenience, they act as acoustic absorbers—essential in open-plan offices and hospitality settings. The Journal of Environmental Psychology (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989) identifies nature exposure as a key contributor to attention restoration, while more recent findings from the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (2019) link biophilic elements to lowered cortisol and improved mood. Moss installations thus function simultaneously as placemaking features and wellness infrastructure.

Layering–a key component of biophilic design. These moss frames are hung atop grasscloth wallpaper in an office that includes large potted plants.

2. Designing for the Rhythms of the Day

Synchronizing with Circadian Rhythms

Lighting has a profound influence on circadian health. The WELL Building Standard and research from the Illuminating Engineering Society confirm that access to daylight and circadian-aligned artificial lighting improves alertness, sleep quality, and overall wellbeing. Morning light can be amplified with reflective interior surfaces and high-performance glazing, while harsh afternoon light can be softened through operable shading, louvers, or electrochromic glass. Tunable LED systems allow architects to modulate spectral output throughout the day, supporting natural circadian cycles.

Designing for Patterns of Use

Post-occupancy evaluations often reveal that occupants congregate in certain zones—near windows, in transitional corridors, or in informal break-out areas. Research by the Center for the Built Environment (UC Berkeley) shows that satisfaction is higher in spaces offering natural light, greenery, and acoustic comfort. By layering biophilic elements into these high-use areas, designers can strengthen both social interaction and well-being.

Multisensory Integration

Stephen Kellert and Terrapin Bright Green both emphasize that multisensory engagement amplifies biophilic impact. Incorporating natural scents through HVAC fragrance diffusers—such as stimulating rosemary in the morning or calming lavender and bergamot in the afternoon—provides a subtle cue that enhances cognitive function and reduces stress. Similarly, acoustic design inspired by natural soundscapes (water features, rustling leaves, or sound masking inspired by natural rhythms) contributes to environments that feel restorative and balanced.

We offer frames, panels, and full walls, and you can order from our panels page, shop standard products, or use our contact form to get your custom dimensions into production.

3. Organic Shapes, Textures, and Materials

Applying Nature’s Patterns to Design Elements

Fractal geometries and organic irregularities are prevalent in nature and can be expressed in architectural form through parametric modeling, biomimetic structures, or organic furnishings. Research published in Frontiers in Psychology (Taylor, 2017) demonstrates that exposure to fractal patterns can reduce stress by up to 60%. Even surface applications such as grass cloth wallpaper or irregularly woven textiles evoke nature’s complexity and invite tactile engagement.

Layering Natural Materials

A biophilic material palette draws from the timelessness of wood, bamboo, stone, moss, and woven fibers. The World Green Building Council’s Health, Wellbeing and Productivity in Offices report (2014) emphasizes that material choices influence both occupant comfort and perception of quality. Layering textures provides depth and richness that mimics the ecological diversity of outdoor environments, strengthening the psychological connection to place.

Moss walls work equally well in traditional office spaces–connecting inside with the views to the outdoors.

Spaces that Evolve with Use

No architectural environment is static. As patterns of use evolve—whether through increased traffic in shared spaces or reprogramming of underutilized zones—design should adapt. Modular moss panels, moveable planters, and organic furnishings allow spaces to grow and change without losing their biophilic integrity. In this way, interior environments remain as dynamic as the people who inhabit them.

Conclusion

Biophilic design offers architects and designers an evidence-based framework that enhances health, creativity, and sustainability. By privileging natural orientation, designing in alignment with circadian rhythms, and specifying organic materials, we create environments that are not just aesthetically pleasing but fundamentally life-enhancing. As Kellert observed, “Biophilic design is not just about bringing nature into the built environment—it is about restoring the bond between people and place.”

For professionals seeking to design environments that are both high-performing and restorative, biophilic strategies are not optional—they are essential. In embracing them, architecture evolves beyond shelter, becoming a living system in dialogue with the natural world.

Endnotes

-

Kellert, S. R. (2008). Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Wiley.

-

Terrapin Bright Green. (2012). The Economics of Biophilia.

-

Kellert, S. R. (2008). Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Wiley.

-

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press; Nieuwenhuis, M., et al. (2014). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

-

WELL Building Standard v2 (International WELL Building Institute); Illuminating Engineering Society (2019). Lighting for Circadian Health.

-

Center for the Built Environment (UC Berkeley). Post-Occupancy Evaluations Database.

-

Herz, R. S. (2009). Aromatherapy facts and fictions: A scientific analysis of olfactory effects on mood, physiology and behavior. International Journal of Neuroscience.

-

Taylor, R. P. (2017). Biophilic fractals and the visual journey of organic architecture. Frontiers in Psychology.

-

World Green Building Council. (2014). Health, Wellbeing and Productivity in Offices.